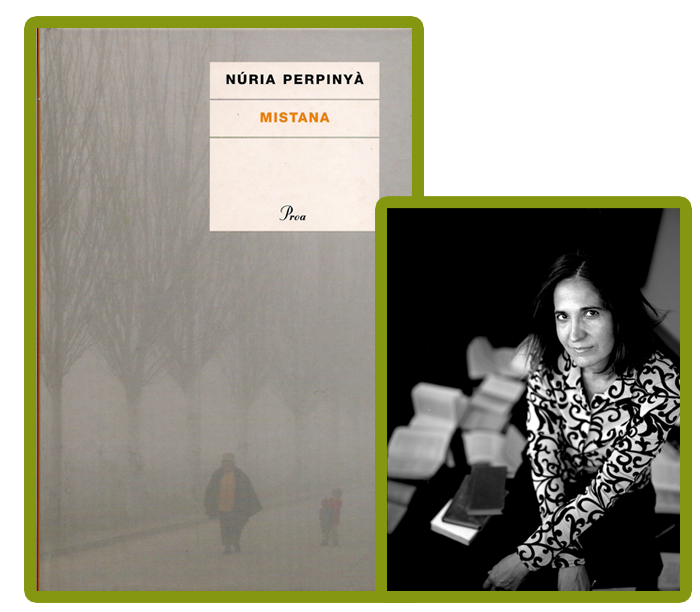

Mistana‘s (2005): Summary

Mistana is a place inhabited by forty selfish and sick people, Quixots and losers who arouse our sympathy and revulsion. Like any enclosed space, this lost and misty town enslaves its inhabitants. Why donât they go to live to a better place? When facing the dictatorship that hangs in the air, every person from Mistana reacts in a different way, from anxiety to frivolity, exemplifying the perspectivist religion professed by Perpinyà . Like the Saramagoâs blind ones and Rulfoâs ghosts, Mistanaâs madmen live in a symbolic space that resembles a Greek tragedy passed through Cocteau and with the air of Fellini’s Satyricon.

The village of Mistana is circular in shape and is nestled in a small Celtic hollow surrounded by menhirs, similar to the one of Avebury, in England. Along the streets, there are water channels, reminding the ones of a Spanish village Candelaria, that merge in the dark with rumors of the conversations.

In the book, the weather with its inpenetrable fog symbolizes the influence of the family and the society over the individual. These influences, hardly avoidable, can be negative and stifling as the eternal fog of Mistana.

However, Perpinyà does not think that the influence of the climate (of the parents or politics) should be deterministic or operate in one direction only. The influence is there, it is quite important, but diverse. For some people, the fog of Mistana is tragic, for others lubricious or spiritual. The villagers behave as spa sybarites, but also as lost blindmen; in order to understand the feeling of blindness the author becomes a regular reader in the libraries for blind.

Moreover, Mistana is a tragedy about motherhood and dead children. It is also undoubtely a reflection on madness. The village is a forgotten and secondary place. Its protagonist, Simbert, is a loser. While In a Good Mistake, Perpinyà reconsiders Aristotelian punishment for a mistake, here the author fully endorses it. Jofreâs erotic escape with Sendal has a disproportionate impact as in Greek tragedies.

NÚria Perpinyà builds this fantastic story about family and madness with a rhythm in crescendo that falls like an avalanche. Mistana is a poetic novel written in a delirious language, steeped by verses in prose that magnetize its readers. Perpinyà was considering to skip the aesthetic prohibition that, until now, has willingly complied: the consonant rhyme. Its sound in the novel, sometimes almost cacophonous, gives to the novel the ugliness and metaesthetic contradiction, adequate for madness. The labyrinths of echoes and resonances of poetic prose express the mental labyrinths of the characters and provide the legendary air of a romance. The puns in A house to Compose had a musical fucntion; here they symbolize the obsession. This expressive resource disappears in the later books of the author.

The fog in literature and art

The books where fog plays an important role are of a poor quality. This was the unexpected conclusion that Perpinyà did after investigating in the literary tradition of the fog. She had two options: to change the fog symbol for another one or to improve it. Well thought, the field was virgin. Apart from some exceptions such as the surrealistic Naval patrol through the fog by Calders; the philosophical mist âNivolaâ by Unamuno; or occasional poetic mentions, no writer had dealt with this climate in depth and dignity it deserved. The author refused to believe that the fog was not guilty of anything. Maybe, it was all a fault of Aristotle who, in The Metereologica, said âthe fog is a sterile cloudâ and a âsecondaryâ phenomenon. Perpinyà had to dissociate the fog from all the negative clichÃĐs and to recreate it beyond the ghosts and science fiction. Despite being aware of having entered an unknown misty forest, in the lyrical passages, Mistana could resemble Turnerâs blurred paintings with music by Debussy in the background. The artistic recreations of this phenomenon have higher quality than the literary ones. The following examples prove it: âA fog buildingâ by Fujiko Nakaya; âA room of thick fogâ by Veronica Sanssens; a sculpture by Diller and Scofidio installed on Lake NeuchÃĒtel (âRingâ, 2002), a kind of a âheaven gateâ or a violet cloud of âTransâ by Stockhausen, that represents a music bridge with the previous book by Perpinyà .

The Satyricon by Petronius (Ist century, Neroâs period) is not related to Mistana, despite the sexuality of the baths, but Felliniâs movie under the same title does. Starting from the common point of men who get lost in fog and arrive to a brothel. The film, splendid, is a mixture of Cocteau passed through Greeneway, while Petronio’s work (if Latinists let us to opine) relates a sassy feast that turns to be boring.

The fog of Lleida

The Mistana fog has also an autobiographical dimension. NÚria Perpinyà Filella was born in Lleida, a town famous for its winter fog. The fact that Lleidaâs fog was always criticized by its inhabitants called Perpinyà âs attention, because for her the fog was beautiful and literary. It could be considered as one of the few things that give character to the place. The fog confers personality to a bland town and brings it into brotherhood with other misty places in the world.

In Mistana, Perpinyà adopts the same literary engineering principle as in A Good mistake: to reverse the hypothetical flaws and turn them into virtues. The fogs of Lleida and Mistana have aesthetic energy that cannot be ignored or overlooked. When there is fog in Lleida, it is no drama: it may not be practical but it is a beautiful sight.

Further on, the autobiography is blurred. Lleida only serves as a setting for the inspiration. Nothing further from the intention of the author and reality than to contend that Lleidaâs people are crazy, unsuccessfull, libertine or mystical.

Was the misty smoke from London or from Charles Dickens?

London. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, wadding like an elephantine lizard up the Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from the chimney -pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes-gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun.

Charles Dickens, Bleak house (1853)

Magi Morera, âWanderingâ (London, June 1914)

Nothing here talks to me about the beloved land.

How far I am from the cradle of yesteryear!

All that I feel and see is a strange to me:

Neither this sky is mine, nor this sun.

My eyes open until it hurts,

In the effort to accommodate so many blessings:

But… , I think of my humble Lleida and…Â no!

All this is not mine, although itâs better.

I am seeking, wandering, for a family flower,

Or some spark of warmth of a homeplace.

And I randomly incline my eyes, and my heart breaks

A bank of fog on a huge river…!

And I see my Segre and its foggy winter…

And I kiss the Thames for a pious memory.

About the psychological influence of the climate

The main character of Mistana is a meteorologist, Simbert Orhiac. He is not the only one. On the canvas of the book there are many more, such as E. FontserÃĻ or V. Sureda. The book pays tribute to the authors who have studied the relationship between art, nature and climate, from the eighteenth century to the present: Tardieu, L. Dufour, A. Galceran, RodrÃguez del Castillo, E. Conde, M. Palomares, etc. Some of these theories are outlandish and unscientific and, for that matter, the most adequate to the madness of the book. We would like to highlight the outstanding Geopsique (1911) by W. Hellpach, with the subtitle: âThe human soul under the influence of weather, climate, soil and landscapeâ. Despite having been written in the twentieth century, this essay has a romantic connection with Mistana.

Continuously modified by our senses and our organs, we carry, without even realizing it, in our ideas, our feelings and our actions, the effect of these modifications. The climates, the seasons, the sounds, the colors, the darkness, the light, the elements, the noise, the silence, the motion, the rest, all act over our soul.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (XVIII century)

About madness

Mistana is a novel about madness and, in consequence, it is full of dissociations, contradictions and depressions. Properly speaking, Perpinyà sorrounds herself for a few years by intellectuals, psychiatrists and writers who have reflected on madness: J.E.D. Esquirol, W. Styron, D. Cooper, Steinberg & Schnall, O. Sacks, Castilla del Pino, Laing, KrÃĪpelin, Torcuato Luca de Tena, P. Benoit, Erasmus, Sartre, H.P. Lovecraft, Maupassant, Gogol, L.M. Panero, Blanchot, HÃķlderlin, Cioran, and, among others, U. ZÞrn.

The book starts with a quotation that builds a bridge between this novel and the pianist from the previous one, A House to Compose: âThe Princess of Homburg gave a piano to HÃķlderlin. He cut the strings, but not all of them, so many keys could still sound and he could do ad-libs.â Â Bettina von Arnim (1840)

My madness has had no witnesses, no one has realized my folly, only my privacy has been mad. Sometimes, frenzied, Iâve been beside myself. They used to say: How happy you are… And yet, he was a man, consumed from head to toes, at night, he used to run through the streets and shout; during the day, he quietly used to work.

Maurice Blanchot, The Madness of Light (1973)

Mother! Mother! Come help me, please! If I go blind and lose the sense like my father, whatever will become of my son? Oh, I beg you, tell me how we survive our folly!â

Kenzaburo OÃĐ, Tell us how we survive our folly (1966)

In this village there is no electricity

the fuse box has burnt out many years ago,

we are the heirs of a cursed trail,

in fits and starts, from who knows who.

Enric Casassas, âThe Villageâ, We were not (1993)

A tragedy

From the Greek tragedies, Mistana receives two inheritances. One of the genre, rushing into chaos as a result of errors of the virtuous people. The book exeplifies Aristotle’s theory of a tragic hero and shows that it still works; however, with less dogmatism because in the present time, there are other ways to create tragedies.

The second one is the Oedipal background between Ghomar and Simbert. The mother, a languid but authoritative philosopher, has subjugated her son and the entire village. âWhat the mistress is like, so is Mistanaâ. The father is the mayor, Jofre Orhiac, a kind of an anarchist Quixote. The hypothetical king of the village, instead of being killed at the beginning of the work, is muredered at the end. But not because of a misunderstanding.

Compra Mistana Â