A Journey Through the BodyÂ

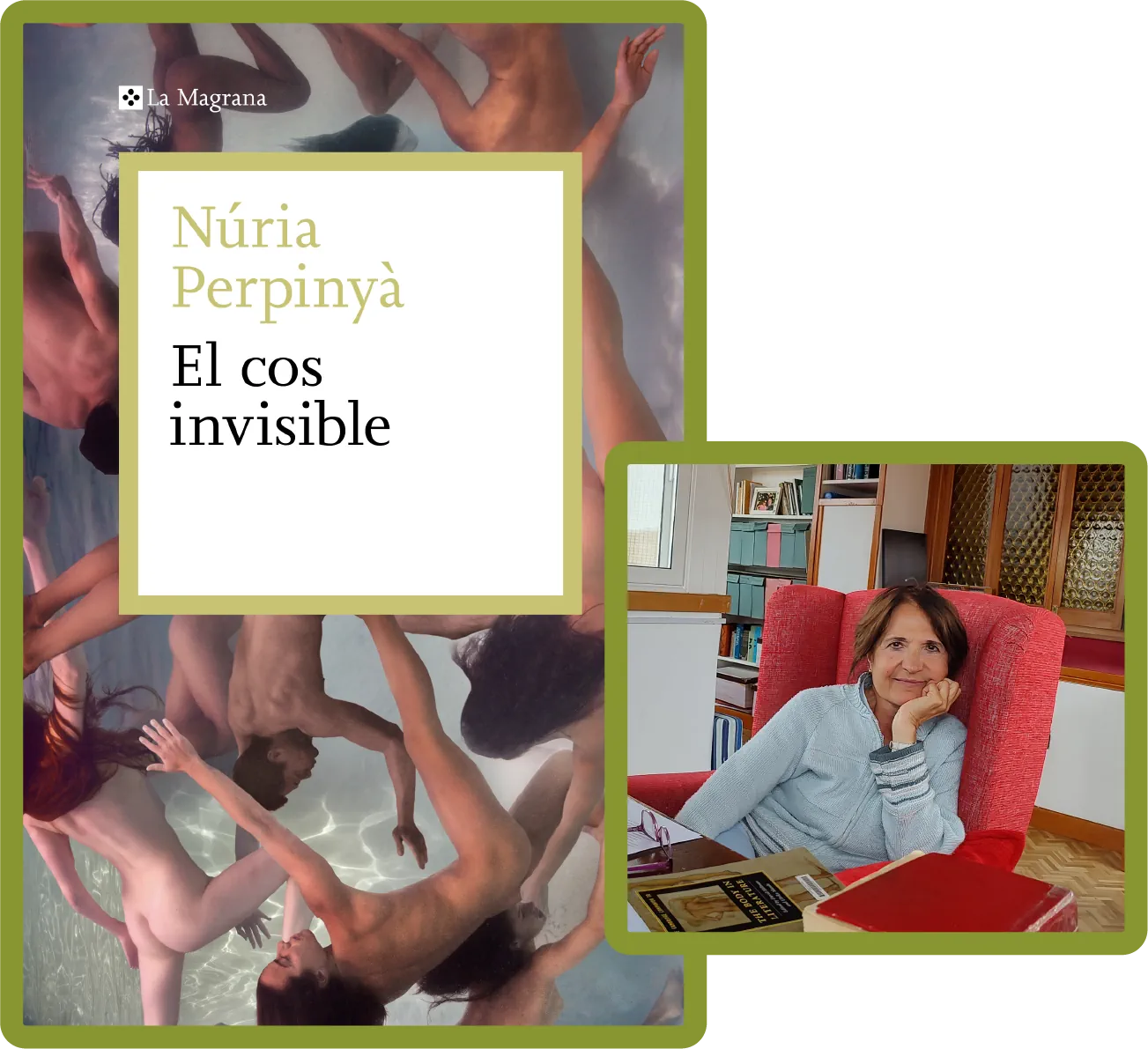

The novel The Invisible Body by NĂşria PerpinyĂ is a fantastic journey into the body, starring a molecule that distributes energy to the entire organism, called Ubis. His ingenuity and his loves are reminiscent of those of Ulysses; and his adventures, those of the Odyssey. The Greek epic lasts twenty years. That of James Joyce’s Ulysses lasts one day. And PerpinyĂ ’s lasts one hour. However, in her novel time expands and becomes an immense hour full of surprises, pleasures and dangers.

Each chapter explains Ubis’ visit to an organ and the adventures that occur as he navigates through the blood, up and down. The narrative is written in a rich and popular Catalan with homages to the Homeric verses of Carles Riba. The tone ranges from comedy (like the episode of Bumphemus, inspired by the Greek Polyphemus) to tragedy (like the visit to the white hell of bones) seasoned with multiple erotic encounters. After all, as it is said in the novel, the obligation of all cells is “to copulate and to suck.”

Although the story is told by a grandmother to her grandchildren, it develops exclusively from the point of view of organs and particles. The novel begins with a kiss that evokes the Trojan War where the girl’s teeth are the walls and the boy’s tongue, the cunning horse invented by Ulysses that manages to penetrate the fortress.

Far removed from the malice and advances of human civilization, these corporeal characters build a world of their own where life is shaped and interpreted in a not usual way. With their help, we discover that the familiar parts of our anatomy and metabolism are, in fact, unknown places. This unusual perspective links this book to the fantastic genre of Calvin’s Cosmicomics, Swift’s noble horses, and Voltaire’s speaking atoms. Despite the personification of the organs, the novel is far from moral fables and children’s literature, since the actions and dilemmas are those of adults and the existential reflections that are resolved, despite being profound, have no didactic pretensions.

We are faced with a humanized body that does not fight against man but rather helps him. Most men and writers are more mystical than they think and present themselves as spiritual men who think about everything except their physicality, which they prefer to ignore by treating it as impure, strange and dehumanized flesh. In PerpinyĂ ’s work, on the other hand, the complexity of biology is admired and the body is thanked for our existence. Instead of presumptuous wise men, we have the modesty and happiness of an entire microscopic universe that is prodigiously organized for the good of a human being.

In this fun and vitalistic novel, the hidden, marginalized and invisible that has been treated as the ugliest and most unpleasant part of existence is vindicated. In conclusion, in The Invisible Body, PerpinyĂ once again bets on perspectivism and invites us to go hand in hand with great classical literature beyond the usual creative limits to build new views that renew literature and the world.

A Humanized Body or the End of Dualism

Most of the thinkers of our civilization cling to what makes them men despite the limitations of the body. Beckett puts many disabled people on stage to explore to what extent a man remains a man, even though the hindrances of an ill body, thanks to language and thought. Language makes the man, not the body. On the other hand, in PerpinyĂ ’s work we do not find a body that ignores language but creates it. Beckett’s body is dehumanized and attacks man, while PerpinyĂ proposes a humanized body that works in our favor because it keeps us alive.

In this book we are far from the flesh despised by Platonism and theologians. Not in vain, ‘somatic’ comes from ‘sema’, which means “tomb.” That is, etymology maintains that the body is a tomb. We find its echo throughout most sacred texts. Buddhism prays that the body may be made insensitive and that the spirit may be favored. Likewise, St. Paul laments: “Who will rescue me from this body of death? With my mind I serve the law of God, but with my flesh the law of sin.” Followed by St. Bernard, for whom the body “is only fetid sperm, a sack of dung and food for worms.”

These disparagements are not only valid for Neoplatonists and religious people. Modern atheist philosophers also share this sentiment. In the 1940s, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty argued about corporality; one in Being and Nothingness (1943) and the other in Phenomenology of Perception (1945). The arguments revolved around the dualism between matter and spirit. Sartre contrasted the ĂŞtre pour-soi (consciousness) with the ĂŞtre en-soi (the body that others see). Sartre’s position was, despite himself, traditionalist and spiritual, since he condemned matter, as we can read in Nausea in his diatribe against a foreign body, that it is not recognized as something belong to him: “I see a tasteless flesh that expands and pulsates with abandon. Starting with the eyes, which, up close, are horrible. They look like fish scales, so glassy, ​​soft, blind and with red edges. (…) I feel my hand. I am these two creatures moving at the end of my arms. My hand scratches one of the legs with the nail of the other leg; I feel the weight on the table that is not me.”

PerpinyĂ ’s attitude is exactly the opposite. She does not show us disgust for the body but rather admiration for it. At the same time, the novelist overcomes the old antagonistic duality and creates a common space in which matter is intelligent and thinks. Her philosophy derives from Merleau-Ponty and his commitment to a non-dualist phenomenology of the body; the French phenomenologist standed up the experience of a perceptive body that is not a simple object, but rather an intersubjective bridge with the world. And she is also obviously the heir of Darwin, who in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) proposed multiple interactions between the body and the mind. “Don’t think about it,” is said when someone is in pain somewhere. It is not just popular wisdom; it is scientific. Darwin explained why when the mind focuses too much on a wound, on a point, it hurts or stings more, because thinking about them sends extra nerve signals. It is the observer’s paradox: that by fixing, you deform the thing, the scene, the action. Darwin was also a leader in the concept of the international body when he demonstrated the physical equality of men above races and genders.

Often, the body knows more than the head. We just have to listen to it. It is fine to talk about artificial intelligence as long as we do not forget natural intelligence. Isaac Asimov, in The End of Eternity (1959), resolves the plot’s knot thanks to the help of the body. Harlan, the protagonist, does not remember where he has lost his beloved assistant, but when he touches the lever of the spaceship again, the hand remembers the gesture he made and repeats it. It is the hand and not the astronaut who knows in what year he left his beloved NoĂżs. However, Asimov was too clever not to know that there are no identical repetitions; and that when one is conscious, one does not make the same gesture. To this complexity of behaviours full of variations, we must add that we are haptic men who listen and speak with our whole body. We are organisms that continuously perceive everything, pore by pore and molecule by molecule, and that compose simultaneous multicellular symphonies.

The literary use of the body has been partial. Despite brilliant comic exceptions such as Gogol’s Nose or Philip Roth’s Breast, its appearance in fiction has been restricted to sex, ageing or the tagged body by race or illness. We must reclaim the totality of our being that makes us and accompanies us, and to leave behind centuries of contempt. As Daniel Pennac says in Diary of a Body (2012), it is time to get to know our terra incognita: “I want to write the diary of my body because everyone talks about other things. All bodies are abandoned in glass cupboards.”

Non-Human Point of View

The protagonists of The Invisible Body are not men. Although they speak of our passions and our fears, their points of view are not human. They are not extraterrestrials or cronopios, even though there is something in common. They resemble Japanese animism, with kami spirits present in all things that animate apparently inanimate objects. And they resemble Swift’s Huyhnhnm horses who do not understand the customs of the YahĂşs or the microorganisms that condition us. In this, they differ from Ubisquinol and the particles of PerpinyĂ ’s novel. In it, we find another tiny Gulliver, a homunculus called Kiddo who lives in the volcano of the ass.

The coenzyme protagonist, Ubis, has the point of view of someone ignorant of the reality,; and also the admiration of the candid who marvels at what he does not know. As Ramon Llull says: “Felix was very amazed that the shepherd was so lazy and so wolflike… While Felix was walking along, thoughtful and eager to know what it is…”

Exploring unknown places

Fantastic novels travel to unknown places. They usually head towards the universe following the path marked by Lucian’s stratospheric man who reached the moon in the first century; and by Voltaire who encapsulated himself within the MicromĂ©gas and reached Saturn where he heard the atoms speak. PerpinyĂ makes the opposite journey, not towards the centre of the earth like Jules Verne, but almost; the novelist takes us inside our body and invites us to the adventure of exploring it hand in hand with a small coenzyme full of energy that reincarnates the Greek Ulysses.

In cinema, journeys inside the body are made by miniature men, as in Fantastic Voyage (1966) or Innerspace (1987). In PerpinyĂ ’s work, a postcolonial point of view is chosen and the protagonists are not the men who colonize the body but the natives who until now had not voice and were despised, the body organs.