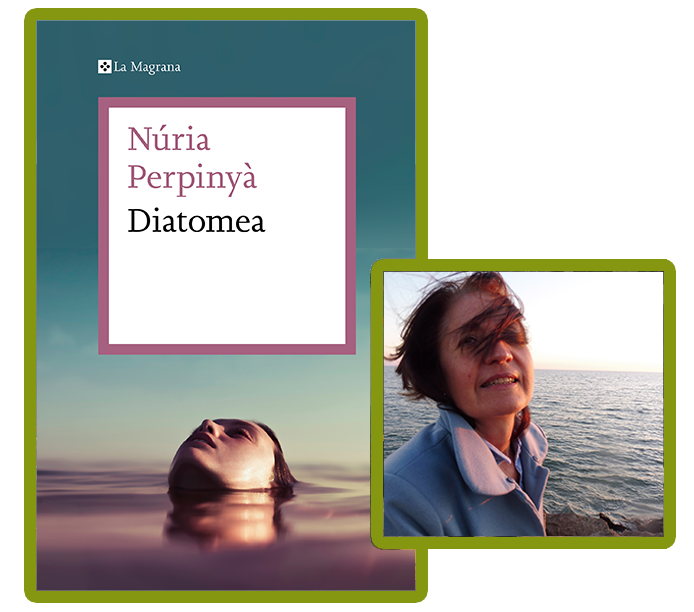

Diatomea or the Blue Colour of the Planet: A Novel about the Sea

The title of N√ļria Perpiny√†’s novel is a tribute to the oceans and to our planet. Moreover, as the title could be associated with an unknown planet, it helps to underline the futuristic nature of the story.

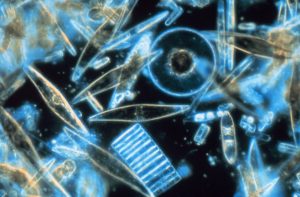

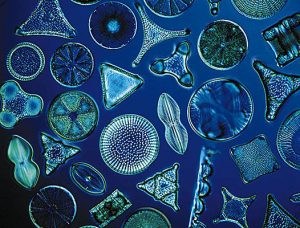

Diatoms are microalgae that nourish the seas and rivers with oxygen through photosynthesis; they are particularly numerous on the surface of the phytoplankton. These millions of single-celled micro-organisms have transparent geometric shapes in shades of green and turquoise blue. Together they form giant crystalline colonies on the surface of the oceans. When the sun shines on these thin layers of plant glass, the light reflects and makes the transparent water appear bluish. Planet Earth looks blue from space thanks to diatoms. It is not for nothing that they are called the jewels of the sea.

The Improvements of the 23rd century: Another World is Possible

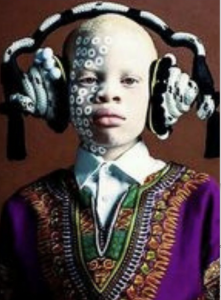

Diatomea (2022) is a plausible futuristic narrative, without monsters or aliens, where there are no more races, wars or traditional food. The world’s population is mulatto. The year is 2216. Boys teach at school ‚ÄĒinstead of being taught‚ÄĒ, robots are part of the family and all politicians are women. Three ideologies prevail in the world: Feminism, Ecology and the Defence of Individual Freedoms. Earthlings enjoy a welfare state where science fiction’s dire predictions of dystopias, apocalypses and totalitarian systems seem not to have come true.

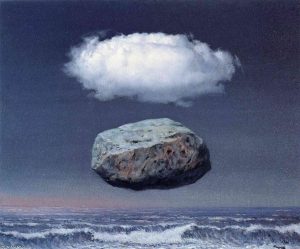

In the novel, children’s fantasy is a cherished value and has a great influence on 23rd century society because it offers unthinkable alternatives to traditional mores. Similarly, dreams are not seen as irrelevant, but their surrealism helps to forge new ideas and react to the unusual; and more importantly, in this Perpinya’s future world, dream activity has been found to be the key to the evolution of humanity; dreams are the transmission channels of the species through which recent and millennia-old experiences are transferred. The novel also expounds a revolutionary theory of non-ephemeral time, illustrated by a sideways moving sand clock, where the grains of the past and the future intermingle with those of the present: “Man is essentially made with ebbs and flows: neither the past is entirely gone nor the present is entirely new. The waters of one and the other mingle in the present. Man is a sum of progressive-regressive actions. We move forward with trials and errors, rectifying and improving”. It is at this point of imagination, that Perpiny√† connects with the best science fiction writers: T. More, Le Guin, Capek, Verne, Asimov, Zamiatin, Orwell, Huxley, J.G. Ballard, Atwood, Crichton, Lem, Mc Ewan, etc.

At the same time, the prominence of the sea connects the author with one of her favourite periods: Romanticism. It is not surprising, then, that between the lines of Diatomea we hear echoes of Byron or Hugo praising the beauty of the azure and the wild energy of the oceans. Likewise, in keeping with the formal refinement characteristic of his style, Perpiny√† here inherits the maritime richness that Catalan writers such as Joaquim Ruyra and Josep Pla. There is also symbiosis with other poets such as the oceanographer Joan Puigdef√†brega: “Island words no longer count for anything; they simply allow themselves to swim with a silent voice that would like to be foam”.

The natura plangens of Climate Change

The mistreatment of Nature is nothing new. For centuries, hominids have used and abused the earth’s resources. In the 13th century, Alain de Lille wrote a lament, a planctus, in which Nature complained about humans. She stated that the whole world obeyed her with only one exception. Plants, rocks and animals respected her, except us. In his¬†De planctu naturae (ca. 1168), Lille narrates a utopia where man abandons his vices and lives in harmony with the planet and the universe. Complementarily, contemporary artists such as Alicia Jeannin in “Water *w√≥rd¬† (Une √©tait la langue #0)” link the sound matrix of the word Water with the origins of Indo-European and the language that join us together.

Diatomea‘s society is almost perfect, it it were’nt for the Climate Change. The temperature of the planet is rising. The melt of the poles and the glaciers of the Alps, the Andes and the Himalayas are causing floods and cataclysms. Fortunately, in the year 2220 the Eco-Warrior are in power.

Innocents turned into Guilty and Absurd Demagogic Solutions

Demagoguery uses sophistical rhetoric to convince of anything; for example, that an innocent person is guilty. The history of the holocaust and the gulags would be sad examples of this. Kafka addressed this misrepresentation¬†masterfully in The Trial. In Diatomea, the innocent water becomes, thanks to Perpiny√†’s novelistic gifts, a murderess.

Likewise, solving political problems with a war is a foolish, irrational, absurd and malignant solution that leaders (especially the violent and presumptuous ones) continue to carry out, despite being so inhumane and counterproductive. Putin’s unwise attack on Ukraine (which has coincided with the publication of this book) is a sample of this tragic senselessness that leads to mountains of ruin and deserts of desolation. In Diatomea there are also crazy and demagogic proposals to improve critical points. After all, it is not literature but reality that, for example, there are plans to bury nuclear waste at the bottom of the oceans. Also, Lissenko’s agricultural plan was sadly historical; it caused ecological disasters (with the approval of no lesser exterminator, Stalin) instead of improving harvests as he promised. Consequently, when the protagonist of Perpiny√†’s novel proposes a radical geological solution (suppressing the seas), although it may seem like science fiction, it is not entirely so, due to human beings have carried out worse barbarities and incongruities than this; the defence of progress and anthropocentrism can be insane and unethical. And the worst thing is that millions of short-sighted people go along with it with conformism. Somehow,¬†Diatomea is a satirical lament against human stupidity.

Characters and Landscapes

All the character of Diatomea are mulatto: The main are: the physicist Bekele Jenklin; his partner, Kailani, a Polynesian perfumer; and their environmentalist daughter, Fronei. As a supporting role there are: the fishermen Menorki (Kailani’s family); Pepa Kalek√∂y (a builder entrepreneur); Carla Tarnizena (an evolutionary biologist); the teacher Siana Tarragovicz; and the robots Ro and Ro5.

The locations of the novel fluctuate between great floods, a futuristic city, deserts, caves and paradisiacal artificial islands. In the middle of the book, a forceful, unexpected landscape appears that as an allegory.

Alternating Plot

Diatomea‘s intrigue is a disturbing mission that sometimes scares and sometimes makes us smile. The absurd has this tragicomic way of being.

In the first part, elegiac chapters alternate with satirical ones on the scientific world; and lyrical seafaring ones with accounts of the remarkable life changes of the 23rd century. In the pages of Diatomea, the music of the water sounds sometimes melodic, sometimes heartbreaking.

The second part starts sixty years later. The rhythm is now one of adventure. The protagonist is the scientist’s daughter, Fronei Jenklin, who is 74 years old. She is the leader of the environmentalist opposition. A persecuted woman and an unusual heroine model: a smart and strong septuagenarian.

It is part of the paradoxes of our species that the beautiful marine diatoms are used to make bricks and dynamite once they have fossilised thanks to the silica in their composition. In this book we witness the struggle between the old oceans and the unstoppable construction industry, a symbol of human progress.

Diatomea in relation to Perpiny√†’s oeuvre as a whole

At this book, we found the author’s characteristic style ‚ÄĒspirals that converge around a theme‚ÄĒ; in this case, the fiction turns around water: from rain and the sea to perfumes and sexual fluids, as well as the torture of the drop by drop. Perpinya’s themes also appear, such as science, teaching, individualism, architecture and the dilemma between chaos and order, some of which are reformulated with irony. The novelty is the prominence of politics and childhood, which were absent in the previous books, with the exception of the lost Mistana‘s girl.

Diatomea marks a turning point in N√ļria Perpiny√†’s career. Without completely abandoning realism, the author opts for an imaginative world, as she had done in Mistana, her unreal novel about fog. Is this a science fiction book? Not exactly. Perpiny√†’s book is, despite its absurdities, a fairly realistic fantasy story. There is, however, a fabulation of the future, an unknown technological world and scientists as protagonists. Also, given the weight of climate change, it can be classified as a Cli-Fi (climate science fiction) book. However, we are left in suspense as to whether it is a dystopia or not.

Diatom is a book of humour and inventiveness of great mental freedom that invites us to escape beyond the limits of the everyday. It is not for nothing that part of this book was written during the confinement of the 2020 pandemic.