Among other reasons, Núria Perpinyà decides to write To the vertigo when she realizes that there aren’t any good novels about mountains. For a creator, a fact of discovering an ineffable new world is a real challenge. Perpinyà proposes to herself to walk through unknown verbal peaks, and to turn a minor genre (the rural picturesque) into high literature. She aims to transmit to her readers the essence of the ideal of mountaneering . She considers that the fiction, unlike painting, still has not well expressed the beauty and attraction of the mountains.

When the climbers write their ascents they usually tend to be boring. Their experiences are unusual but they still don’t have their place of honor in the literature. We hope that To the Vertigo has finally achieved it.

The stories of climbers are generally literary poor. Let’s admit it: some know how to write and others how to climb. The mountaineers’s way of telling is schematic: We climb up, we climb down, we reach the summit, a storm surprises us, we live some critical moments, we overcome them, one of us dies, we have to move forward, we come back. The stories are very similar to one another, without any distinction of peaks, landscapes or feelings. However, there are exceptions. Those who best express their odysseys are Reinhold Messner, Jon Krakauer, Joe Simpson, Greg Mortenson or Martinez Pison. It’s also Maurice Herzog, who experienced and wrote the first and dramatic ascent to an eight thousand: the Annapurna. The book triumphed with eleven million copies. Mountain novels are scarce and most of them written in a rural style. Or, on the other side, they look for a spiritual image of the peaks. Among the most plausible, there is Frison-Roche, a writer from the forties whose books are still bestsellers nowadays. In Catalan literature, the highest poetic mountain peaks belong to Verdaguer and Perejaume.

Poetry, romance and mountaineering: Individualism and Idealism

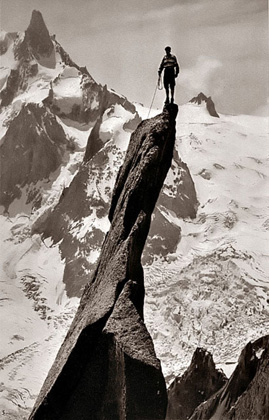

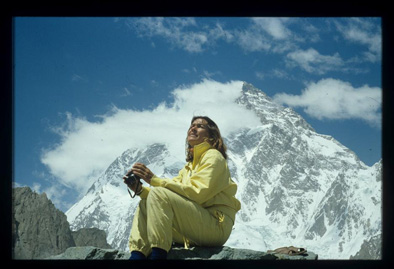

Times ago, an artist was treated like a genius. Nowadays, the best sportmen are treated and laureate like gods. The Olympus of the writers and the Parnassus of the poets are out-of-date. The podium has replaced them. The fact that some athletes are vulgar and uncultured doesn’t blur the process. The Himalayas climbers risk their lives to get as high as possible; they resemble one known greek who wanted to reach the sun. The climbers and writers share a similar incomprehension of the oddity of their profession. Some do strange things; others say them. We are sensible people. What is the utility of a poem? Why people climb to the top of the mountains? We greatly defend the loneliness. We dream worthless deeds. Our worship of nature is overwhelming. Climbers are a reincarnation of those romantics who, at least on paper, used to escape from civilization and wandered through the uninhabited places. The words of ones are transformed into legs of others. The drama is to die too young for having bet too strong. We sacrifice everything for our ideal. One must win or die. We prefer a few passionate months to a long monotonous life. An ephemeral and sublime happiness. An impatient vitality of the youth. Climbing is freedom. We are people who do not want to grow. We never adapt to work or routine life. At Christmas or New Year’s Eve, instead of celebrating with family and a lot of people, we embarked on a solitary winter climb or we share the experience with a very close friend. A moment that we feel like gods compensates everything. The beautiful himalayan climber Alison Hargreaves and her husband claimed that they preferred to live one day like a tiger to one hundred years like a lamb. True to herself, Hargreaves conquered the north face of Everest without oxygen and, a victim of her ideal, died in a storm on K2 at age of 32.

In the nineteenth century men fall in love with the mountains

NĂşria PerpinyĂ knows well the nineteenth century. While writing the novel, its landscape paintings were constantly on her mind. The men did not pay attention to the mountains but one hundred years ago. For centuries they had them beside, but they did not see them. Until, all of the sudden, in the nineteenth century, the most daring ones discovered and fell in love with them. Some were adventurers, with a desire to conquer unknown lands, others were naturalists who climbed the mountains to learn about the formation of the rocks and to collect botanical rarities. The mountain became something magnetic and sublime. A powerful force of nature on the edge between ecstasy and disaster.

The passion for the mountains is relatively modern. Before romanticism, a mountain was seen as heinous and inhuman associated with cold, misery and discomfort. Aesthetically, they were also unpleasant. “Nature has swept all the filth of the earth to the Alps, to form and clean the Lombardy plain” said Evelyn in 1646. And in 1701, Adison riveted: “The Alps make the most irregular and regrettable scenes in the world.”

In the nineteenth century, the general view changes dramatically. The aristocracy and the bourgeoisie go up to spend the summer in the health resorts and spas. The cartographers, geographers, botanists, painters, doctors and engineers practice mountaineering for the sake of their respective professions. Others seek thrills. The mountains are still not beautiful, according to what Whymper says in 1865, but they are great and sublime. Throughout the nineteenth century, the main peaks of the Alps are conquered one by one. The Himalayan ascents begin in the twentieth century.

We hope that reading of To the vertigo will be less harsh!